From: Wanda Coleman/Los Angeles

Date: Sun, 23 Nov 2008 15:21:40 -0800

From: splabman@yahoo.com

Subject: American Sonnets

To: wanda coleman

Wanda,

Good to get caught up with you yesterday. Hope the burn is healed quick. My hoops career imperiled, but I’d be happy to run again, or ride my bike. Old age ain’t for sissies.

W: Good talking to you Paul, as always.

On to American Sonnets. They were first published in 1994 by Light and Dust Books in Milwaukee. These were sonnets 1-24. 26-86 were in 1998’s Bath Water Wine (Black Sparrow) and then 25 shows up, along with 87-100 in 2001’s Mercurochrome (Black Sparrow.) You say there are a couple of others scattered around. What was the initial inspiration for the American Sonnets?

W: I’m not sure. The idea came to me when applying for an NEA grant in the early 70s. The application seemed to suggest that having a project, other than merely writing poems, was more likely to get a favorable response. Also, I had just received some negative criticism/rejection from a literary magazine in the midwest. The editor/publisher told me I was writing jazz poetry. At the time I had no idea what he meant. How was jazz poetry distinct from any other poetry. I didn’t get the NEA on that go-round. I set the incidents aside; however, they apparently were at work in my deep consciousness, and a decade later the first sonnet appeared unbidden. I recognized it and they were off and running, coming at undetermined intervals. Sometime in the late 80s I reread all of Shakespeare’s sonnets, sonnets by Melville and others and decided I was certainly capable of doing a series of them. All that was left was to work out my criteria.

Sonnet comes from an Italian word for little sound or song. In the era of Open Form, the sonnet has come to be a 14 (or so) line poem which encompasses a method of thought. Is this a sufficient definition for your sonnets? If not, how do you define the American Sonnet?

W: Since jazz is an open form with certain properties–progression, improvisation, mimicry, etc., I decided that likewise the jazz sonnet would be as open as possible, adhering only to the loosely followed dictate of number of lines. I decided on 14 to 16 and to not exceed that, but to go absolutely bonkers within that constraint. I also give the sonnets a jazzified rhythm structure, akin to platter patter and/or scat and tones like certain Beat writers such as Kerouac, Kaufman and Perkoff. I decided to have fun–to blow my soul.

I read #12 again and marvel at its ferocity. Two questions: One, you wrote that after Robert Duncan. Do you remember how that came to happen?

W: Thanks, Paul. I’m frequently a casual reader. That is, I’ll pick up a book at home or someplace else and casually begin reading through it in no particular order, letting some word, poem or writer snatch my attention. If the impulse is strong, sometimes it sets off a poem in me in response to what I’ve just read. That’s what happened with Duncan. It’s not something I set myself to doing, it simply happens.

Two, do you find that ferocity, when squeezed into 14 or so lines, is a key to why these poems are so successful?

W: Hahaha, Paul. I’m jes’ fierce by nature.

Jack Kerouac likened his writing process to the spontaneous composition he experienced watching bebop being performed. Not only are there multiple references to Jazz artists like Billie Holiday and John Coltrane in your work, but you are one of a handful of poets whose work IS Jazz. It has that spontaneous freshness, though I know you have a revision process. The American Sonnets seem to hold a ferocious kind of riff in them. Do you agree? Can you elaborate?

W: Well, I think I covered this above, but yeah. I often mimic the rhythms of my subjects. I’ll do a Miles Davis riff or a Holiday riff depending. Remember, I have a background as a musician. I initially studied the piano and violin and wanted to be a concert violinist when I grew up. (I can sight read, if not as good as I once was. And I can still pick out a tune on the piano when it is available.) That did not happen as a result of a brain fever (encephalitis) around my 11th birthday. I lost some motor acuity on my left. I also had voice training and am quite a singer when in voice. I wanted to do that too, but opted out when I felt I had nothing original to bring to that particular art. So I have put all of my musical ambition into my writings–including the sonnets.

Does it come spontaneously using the trope of repetition in a poem, or do you go into the act of composing with the notion that a certain word is going to provide a foundation (rhythmic and otherwise) such as the word Jailer (#85) and Mayday (88)?

W: Paul, I’ve haven’t read these in awhile, so it is a trip checking them out. The image of society as a prison runs throughout my work, fiction too, so it was on my mind and came spontaneously in #85. When calling for help (I believe the American expression mayday is after the French world for help), there is usually a natural repetition related to urgency. I repeat it three times as I’m won’t to do–which, in my case, is adapted from listing to the ministers of my childhood church-going days. They usually did it 3 times–like magicians counting to three–as if there were some conjure value in the process.

What other sonnet writers resonate with you?

W: Frankly, not many. Because strict formalists tend to allow the form to dictate their language so that their series of sonnets become uninteresting after the first few. It’s difficult to sustain this kind of energy in the second place. I’ve read some interesting contemporary collections in manuscript form when sitting on grantsmanship panels in the past, but I don’t remember who those writers were, or whether or not their work was ever published. My title American Sonnet seems to have inspired others, like Billy Collins, to borrow my title for their own sonnets without giving me a nod. Gerald Stern did a series of American Sonnets with 52 lines–too many lines in my estimation, but a gutsy effort.

How would you give the assignment to write an American Sonnet?

W: First I would explain my process. Then I would invite my students to try it, overlaying their specific 1) issues (what the sonnet is about) 2) rhythms (places and devices often have them) 3) tones (shadings of attitude) 4) musical taste/preference (rock, classical, blues, etc.)–how to develop the minimal language to simultaneously encapsulate and signal each.

Take your time on this, Wanda. I am very grateful.

W: Gotta run. The demons are stirring….hahaha.

Paul

Paul E. Nelson

Global Voices Radio

SPLAB!

American Sentences

Organic Poetry

Poetry Postcard Blog

Ilalqo, WA 253.735.6328

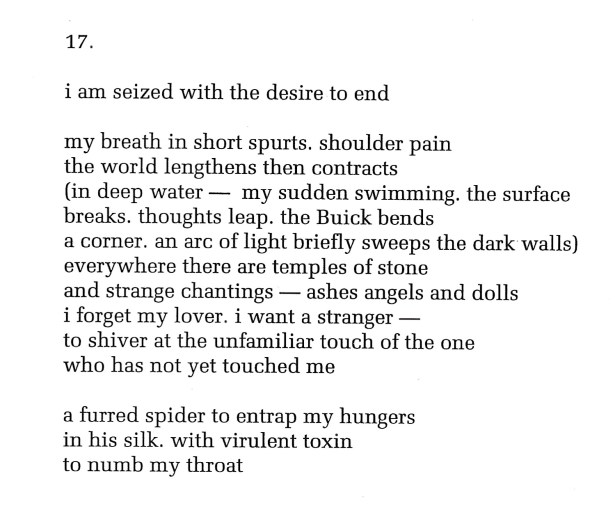

Read #12 and 17 from American Sonnets, 26, 51, and 85 from Bathwater Wine, 88 and 96 from Mercurochrome.